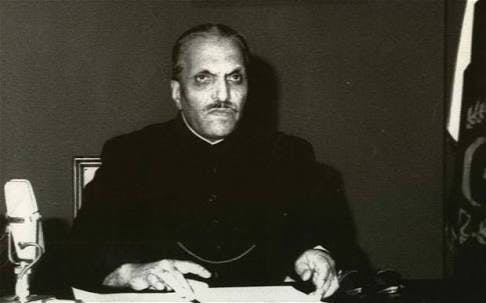

Did General Ziaul Haq know his end was near?

Today was the day when, 38 years ago, General Ziaul Haq overthrew the Zulfikar Ali Bhutto government and imposed martial law in Pakistan.

Three things come to my mind when I think of General Zia.

1977

The Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) movement against Bhutto.

I belong to a religious family. My late father, Muhammad Abdullah, a religious scholar and a fiery fighter against forces of oppression, would take part in every struggle.

He did that against the British in 1940s, where he was jailed in solitary confinement and had to go on a hunger strike to near-death position which later led to his release.

This time it was against Bhutto. He, like everyone else in this country, was fed that it was a battle between Islamic forces led by pious Mufti Mahmood of PNA and a secular, wine-drinking Bhutto.

My father’s natural alignment was against Bhutto.

As a child I accompanied him to these protest processions. Several times, I saw him being baton-charged and tear-gassed. I too would get an occasional hit. Months of agitation led to a martial law imposed by Zia. Precisely as he orchestrated. Zia had achieved what he planned.

Early 1980’s

As a shrewd dictator, Zia was bent on eroding all existing political powers so he would face no threat to his power position in the immediate term.

In that process, he found a fiery man in Karachi and brought MQM to the fore to destroy Jamaat-e-Islami (which under later compulsions chose to be his notoriously known B-Team and thus lost all future credibility).

In much of the Punjab, Zia tried to create an alternate leadership. My father was merely an activist (and not a people puller). He had no liking for a power-holder Zia. He wouldn’t even meet an official because under his belief system, an aalim should not rub shoulders with those in power.

However, our family was kind of influential in our own way: religious leadership through madrassahs.

My mother, Aapa Amtur Rasheed (born 1928), ran a residential Madrassatul Banat in Faisalabad, which in the early 1980’s was the largest residential facility in Pakistan for girls seeking Islamic studies in Quran, Hadith and Arabic grammar. Started in 1966, it is now an examination centre for the Wafaqul Madaris exam (equal to an MA degree) for girls.

Until then, madaris were not used for domestic terrorism. These were merely places as an alternative platform for eduction, different from traditional schools and colleges.

In order to develop alternate leadership, which later took the shape of Majlis-e-Shura (Zia’s version of Parliament), my mother was approached. Zia wanted to meet her.

At that time, known as perhaps the biggest female scholar of Islam in the country, she too was a bit unsure how to respond.

I remember several visits happened to our place: started in 1981 with local MP Mrs Colonel Nusrat Maqbool Elahi. Then in 1982, Federal Minister Afifa Mamdot and in 1983, Federal Minister Atiyya Inayatullah visited within a space of a year. On a separate occasion, MP Aapa Nisar Fatima (mother of current Federal Minister Ahsan Iqbal) and Mrs Kulsoom Nawaz Sharif (wife of current Prime Minister) also met my mother.

But the biggest guest to visit our place was Mrs Shafiq Jahan, Ziaul Haq’s wife, bringing Zia’s message. This was perhaps in 1984.

In the conversation, Mrs Zia could gauge that my mother was not the MP material and had no interest in politics or the limelight. All she wanted was to continue doing what she did for decades in low-profile: teach girls knowledge about Islam.

Although some people close to our family did opt to be member of Majlis-e-Shura while a few others chose to stay behind the scene and become what is called the king-maker role.

Mid-1980’s

I chose Karachi University over Punjab University for a masters in Mass Communication. I had two occasions to listen to Zia at a venue what’s now called Regent Plaza Hotel. On one occasion, Zia granted MA degrees to our senior batch of MassComm graduates.

I remember on one occasion, circa 1986/87, Zia made a passionate speech against the then journalist Mushahid Hussain (now a politician with PML-Q) who he said had disclosed our nuclear secrets to Indian journalist Kuldeep Nayyar.

On his prompt, the crowd demanded that Mushahid must be hanged for this treason. In the audience, in my naivety, I was like: How come a powerful President needs to move the audience to the outcome of his liking. He’s the President. He can just hang him.

Didn’t know the workings of power play: then and now.

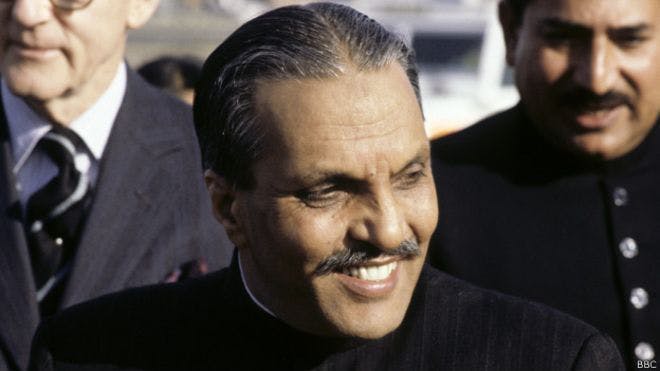

When I met Zia face to face, he had all the charm of a forceful person.

At that time, I was writing a weekly campus diary for The Morning News (an English-language newspaper Quaid-e-Azam had founded along side Dawn; the paper later died) in English and for Daily Jasarat in Urdu.

I remember when I reported the Regent Plaza event and wanted to add a line of praise for Zia’s warmth and firm handshake, my editor, who apparently didn’t like Zia, struck it off. I asked why. He said you are just a kid and may have been overwhelmed by the dictator. When you grow up and know the real man, you will regret this line. How foresighted!

August 1988

Zia, in all likelihood, knew that his time was up. He knew how power play worked.

At that time I was working at the news desk of The Nation newspaper in Lahore.

Apparently knowing well that his end was near, Zia invited a team of editors from The Nation and its sister Urdu daily Nawa-e-Waqt which included Chief Editor late Majeed Nizami, Editor Arif Nizami and Chief Reporters for what came to be known as Zia’s last interview. This was on 13 August at Army House Rawalpindi.

In that interview, Zia wanted to present his version of the events in his 11-year tenure.

The Nation had planned that the interview will be published in next weekend’s magazine. That weekend never came in Zia’s life.

17 August 1988

Then the midair crash of C130 happened in Bahawalpur.

The interview script was not yet ready. The Nizamis pushed the deadline forward – to today.

Editor Arif Nizami decided to run the interview or at least a summary of it, in next day’s paper along with the lead news of air crash and Zia’s death.

I then had a reputation for fast-speed, accurate editing and headlining, so the feature piece comprising of Zia's last interview came to me. I edited it and headlined: ‘Prophetic Zia hoped history would regard him objectively’.

My news editor looked at the headline, struck off the word ‘prophetic’, and said to me: ‘Prophetic’ could be misinterpreted by our religious zealots.

So the interview headline ran on the Front Page next day was: ‘Zia hoped history would regard him objectively’.

Indeed it did.

Wali Zahid

Wali Zahid is a longtime China watcher and a Pakistan futurist. An award-winning journalist, he writes on issues of significance to Pakistan and CPEC & BRI.

Related posts